History of the French Marine Nationale's mariniere

The history of the French National Navy mariniere as we know it today begins in 1850 following a Navy decree.

The decree issued in 1858 by the French Navy: birth of a uniform

The striped shirt as it is called by sailors or the "marinière" as it would later be called for the general public only, has become the symbol of the French military navy, and is the image of sailor style.

It is often said that the purpose of the stripes was to better spot sailors in case of a man overboard, but in reality thisʼs not true. The explanation is older and comes from the tradition of seafarers to wear striped shirts.

Before the XVIIIth century there was no true uniform on the ships. The sailor-men were drafted (often by force, given the rough conditions of life aboard) with their own garments, making the crew looking very heterogenic. This was problematic during naval boardings or visual identifications (like differentiating pirate-ships and warships).

During the second Empire (rein of Napoleon the 3rd) the Ministry of War issued a decree, on the 27th of May 1858, to standardize the sailor-men’s uniforms. This shirt will end up being provided directly by the Navy.

The norms were mere: the shirt should feature on the body 20 or 21 stripes in waid blue, wide of 10mm, and spaced each of 20mm (the double of one stripe); on the sleeves 14 blue stripes. The sleeves must be three-quarter-long, to remain below the smock sleeves. It should feature also a boat neck, just underneath the neck. The decree also ruled that all men (boatswain, Quartermasters, Helmsman, boys and sailors) will be provided with two cotton-shirts each semester.

The stripes enabled to differentiate the petty officers or sailors from the high-ranking officers. The wide and colours of stripes enabled to determine the nationality of each sailors.

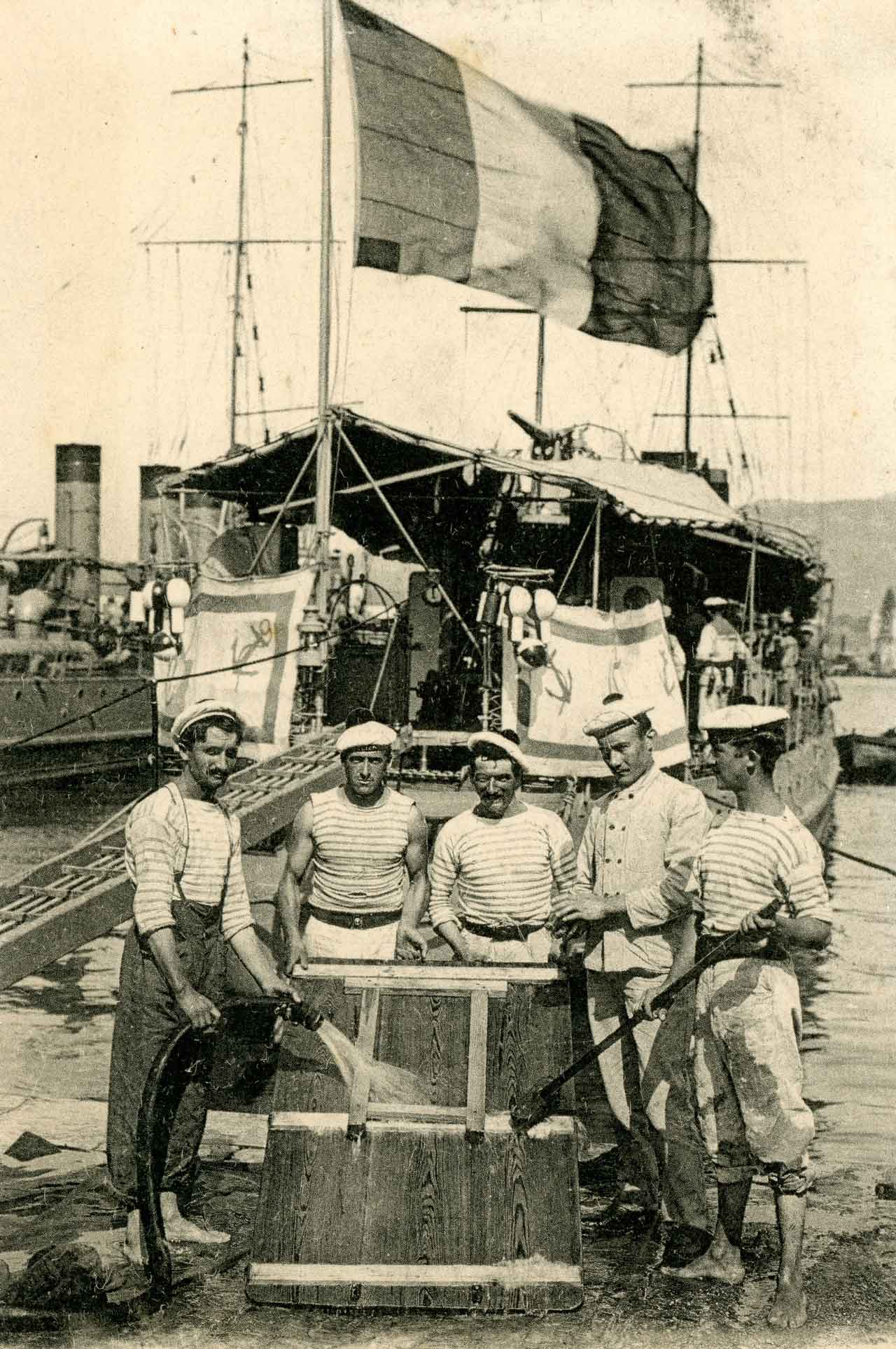

The striped shirt is an underwear-workwear garment, for every day’s labour. It became quickly a staple of the uniform of sailor men/servicemen. With the spreading of photography, the marinière turned to be inseparable of the sailor’s look.

Many believe that the number of stripes was a reminiscent of Napoleon’s victories or to spot sailors fallen in the sea, but it is a navy legend…

The military service at sea

From 1798 to 1997, the army required every man aged from 18 to 25 years-old to join the army for one year.

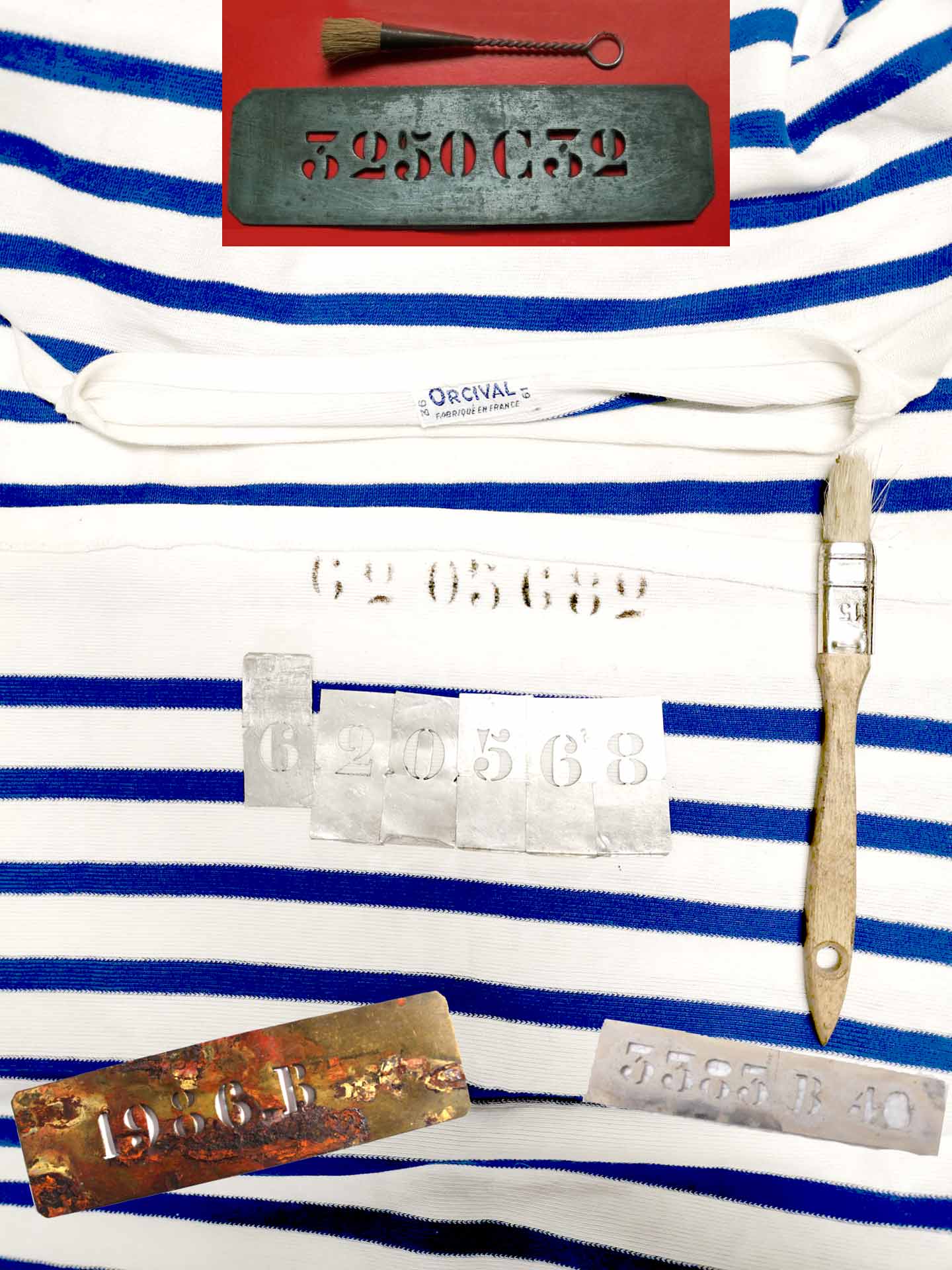

The need for marinières to outfit all sailors was tremendously growing each decade, following the growth of population. Each sailor has two Breton shirts, replaced each semester. At the end of his service, the young man proudly keeps his marinières, inked with his army service number.

Based in Lyon in 1940, Orcival supplied the naval base of Toulon (on the Mediterranean Sea). As modern warfare required France to have a global presence and power projection, the Navy staffing boomed, and Orcival manufactured large amounts of marinières (uniforms and spares) now available in second-hand shops.

The service number and the marinieres

The service number is key to date a Navy striped shirt thanks its rules of “construction”.

The matricule number is the number assigned to each member of the French army upon incorporation, i.e., upon entering the army.

The decree of the 4th of May 1970 specifies that every sailor has to mark down his own tops. In 1891 the Navy supplied its sailors with copper or brass service number plates. From 1924-1928 a new rule issued that every service number should start by 0 (reset) each 1st January. From 1928 to 1952 new rules standardized the “resume” of the sailors, featuring his year of draft and home port.

In 1952 Toulon naval base became the GHQ of the French Navy, a boon for Orcival. Thus, the base turned to be the one-stop registrar. In 1962 the numbers are automatically created, and in 2000 the year of draft is entirely comprised in the number.

Along with the plate the sailors received a brush with a bottle of indelible ink to mark every garment: bags, smocks, caps, pants… to enable to match each garment and sailors after collective laundries, or identifying the sailor in case of death. The plate was in one piece, avoiding any mistake of marking.

The number font was also idiosyncratic: it comes with “French numbers”, enabling to identify the service number or the sailor nationality by a foreign serviceman, after capture or shipwreck.

Fashion and the sailor suit

During WWI, Coco Chanel, inspired by local sailormen she saw in the seaside resorts where she used to spend holidays, marketed in her second shop in Deauville the Basque Shirt. It was the first time that marinières were retailed, plus amid top-notch garments. The top fit her strategy to “free” women’s bodies with an ample tee-shirt, while using a fabric easily available in these times of wartime shortages: she bought the jersey at Rodier’s (a fabric supplier for haute-couture brands founded in 1848).

Stripes became the new black in the Parisian high-society then went mainstream in France.

Later on Karl Lagerfeld recalled the legacy of Coco Chanel by using Basque shirts in S/S collections for so-called « Cruise » fashion shows. But Yves Saint Laurent was the first one to use the marinières frequently in his fashion shows along with peacoats or other sailormen’s clothes.

From the 1950’s marinières really won recognition as a fashion staple. In the next decade movies stars as Jean Seberg featured in À bout de souffle movie, Brigitte Bardot featured in Le Mépris movie, wore the Breton shirt. Next Jean Cocteau, Pablo Picasso, Brigitte Bardot, le Mime Marceau were pictured in a striped shirt.